Modern Mercurial - Phases

This post is part of a series named “Modern Mercurial” where I share my realizations about how much Mercurial has advanced since 2005 without me noticing.

Last year, I had a realization that I haven’t been using Mercurial to its full potential. In this post, I’d like to share my thoughts about and usage of Mercurial Phases.

Phases are not a new feature. They made their first appearance back in 2012 as part of Mercurial 2.1, which makes them a little over 6 years old.

What are phases?

While there is a description of phases on the Mercurial wiki, I’ll take a stab at a short intro.

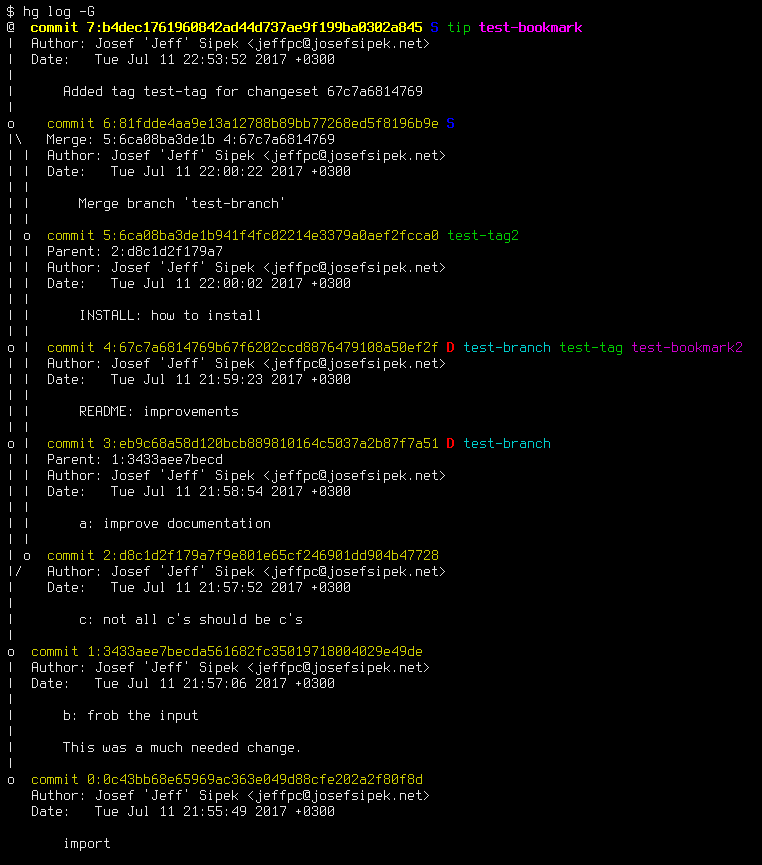

Each commit belongs to one of three phases (public, draft, or secret) which implies a set of allowed operations on the commit. Furthermore, the phase dictates which other phase or phases the commit can transition to.

You can think of the phases as totally ordered (secret → draft → public) and a commit’s phase can only move in that direction. That is, a secret commit can become either a draft or a public commit, a draft commit can become a public commit, and a public commit is “stuck” being public. (Of course if you really want to, Mercurial allows you to force a commit to any phase via hg phase -f.)

The allowed operations on a commit of a particular phase are pretty self-explanatory:

Public commits are deemed immutable and sharable—meaning that if you try to perform an operation on a commit that would modify it (e.g., hg commit –amend), Mercurial will error out. All read-only operations as well as pushing and pulling are allowed.

Secret commits are mutable and not sharable—meaning that all modifications are allowed, but the commits are not pullable or pushable. In other words, a hg pull will not see secret commits in the remote repository, and a hg push will not push secret commits to the remote repository.

Draft commits are mutable and sharable—a phase between public and secret. Like secret commits, changes to commits are allowed, and like public commits, pushing and pulling is allowed.

Or in tabular form:

| Phase | Commits | Sharing |

| public | immutable | allowed |

| draft | mutable | allowed |

| secret | mutable | prevented |

By default, all new commits are automatically marked as draft, and when a draft commit is pushed it becomes public on both ends.

Note that these descriptions ignore the amazing changeset evolution features making their way into current Mercurial since they can blur the “not yet shared” nature of draft commits. (Perhaps I should have titled this post Modern Mercurial (2012 edition) — Phases.)

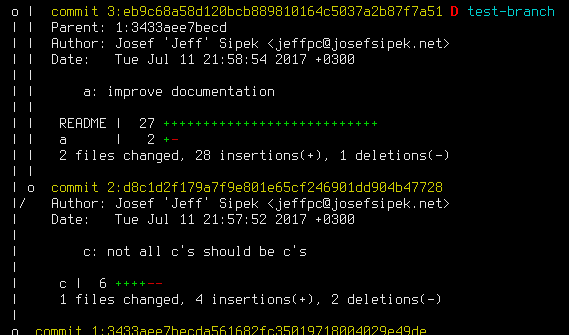

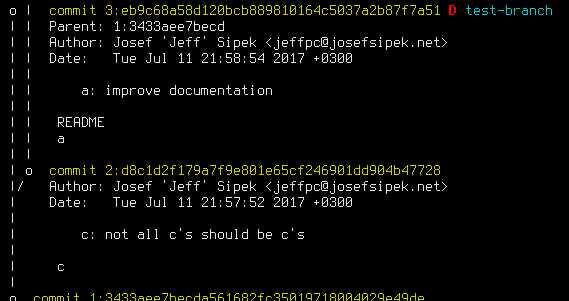

A note about hg log

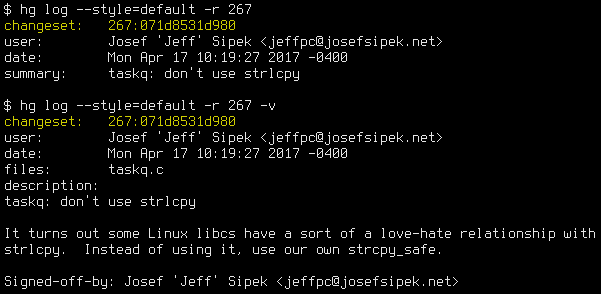

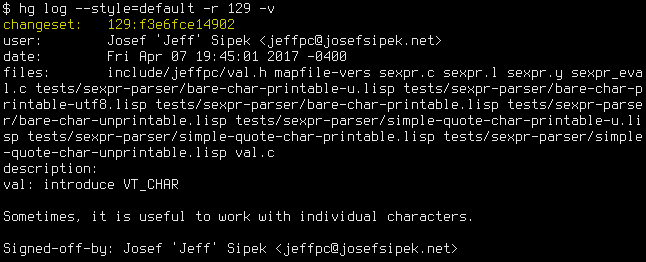

Unfortunately, the default hg log output does not display phases at all. I think this is rather unfortunate (but understandable from a backwards compatibility point of view).

Last year, I dedicated a whole post to how I template hg log information including my reasoning for why I display phases the way I do.

How do I use phases?

Now that we have the basic introduction to phases out of the way, let me describe how I mapped them to my workflow.

First of all, I make all new commits start in the secret phase (instead of the default draft) with a quick addition to .hgrc:

[phases] new-commit = secret

This immediately prevents an accidental hg push from pushing commits that I’m still working on. (Recall that secret commits cannot be pushed.) In at least one repository, this allowed me to regularly have more than 6 heads with various work-in-progress feature ideas without the fear of accidentally messing up a public repository. Before I started using phases, I used separate clones to get similar (but not as thorough) protections.

Now, I work on a commit for a while (keeping it in the secret phase), and when I feel like I’m done, I transition it to the draft phase (via hg phase -d). At that point, I’m basically telling Mercurial (and myself when I later look at hg log) that I’m happy enough with the commit to push it.

Depending on what I’m working on, I may or may not push it immediately after (which would transition the commit to the public phase). Usually, I hold off pushing the commit if it is part of a series, but I haven’t done the last-chance sanity checks of the other commits.

Note: I like to run hg push without specifying a revision to push. I find this natural (and less to type). If I always specified a revision, then phases wouldn’t help me as much.

“Ugly” repos

I have a couple of repositories that I use for managing assorted data like my car’s gasoline utilization. In these repositories, the commits are simple data point additions to a CSV file and the commit messages are repetitive one-liners. (These one-liners create a rather “ugly” commit history.)

In essence, the workflow these repositories see can be summarized as:

$ echo "2018-04-05,12345,17.231," >> data.csv $ hg commit -m "more gas" $ hg push

In these repositories, I’ve found that defaulting to the secret phase was rather annoying because every commit was immediately followed by a phase change to allow the push to work. So, for these repos I changed new-commit back to draft.

Edit: I reworded the sentence about Mercurial giving you a way to force a commit to any phase based on feedback on lobste.rs.