This post is part of a series named “Modern Mercurial” where I share my realizations about how much Mercurial has advanced since 2005 without me noticing.

As I pointed out recently, I ended up customizing my .hgrc to better suit my needs. In this post, I’m going to talk about my changes to tailor the hg log output to my liking.

There are three issues I have with the default hg log format:

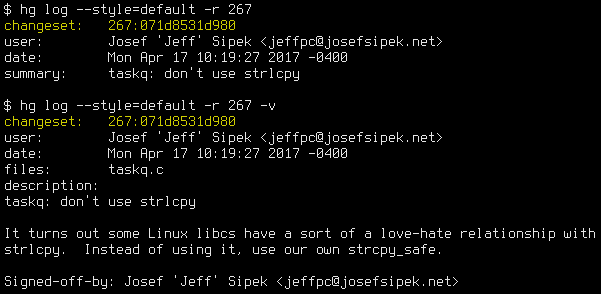

- By default, only the first line of the commit message is shown. To see it fully, you need to use verbose mode.

- In verbose mode, the touched files are listed as well without a way to hide them.

- In verbose mode, the listed files are not listed one per line, but rather as a single line.

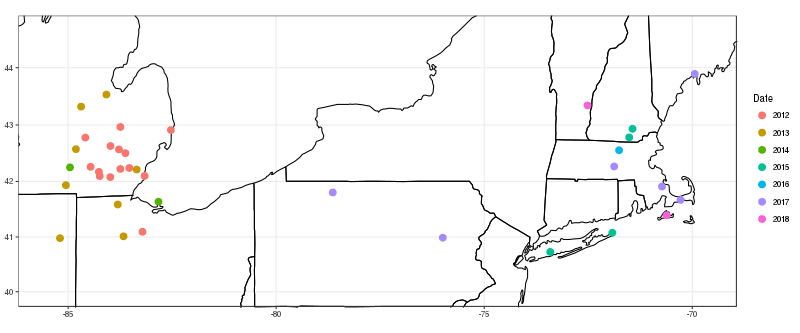

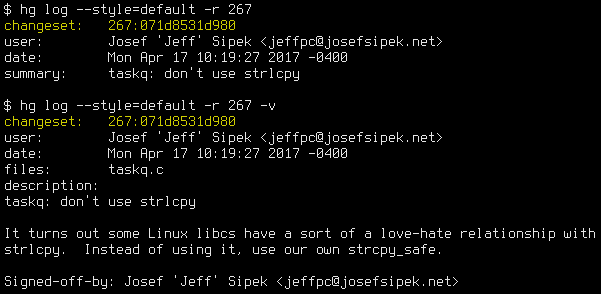

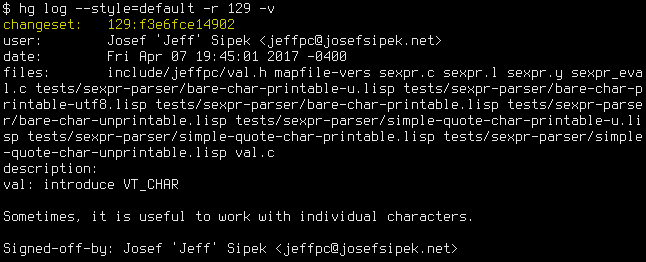

If, like me, you prefer the Linux-kernel style commit messages, you likely want to see the whole message when you look at the log (problem #1). Here is, for example, a screenshot of a commit using the default style (normal and verbose mode):

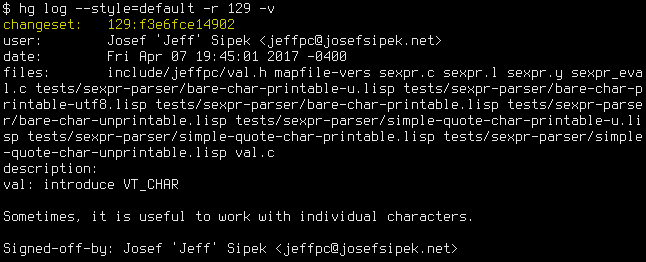

You can work around not seeing the whole commit message by always using the verbose mode, but that means that you’ll also be assaulted by the list of changed files (problem #2) without a way to hide it. To make the second problem even worse, the file names are listed on a single line, so all but the most trivial of changes create an impossible to read blob of file names (problem #3). For example, even with only a handful of files touched by a commit:

At least, those are my problems with the default format. I’m sure some people like the default just the way it is. Thankfully, Mercurial is sporting a powerful templating engine, so I can override the style whichever way I want.

Demo

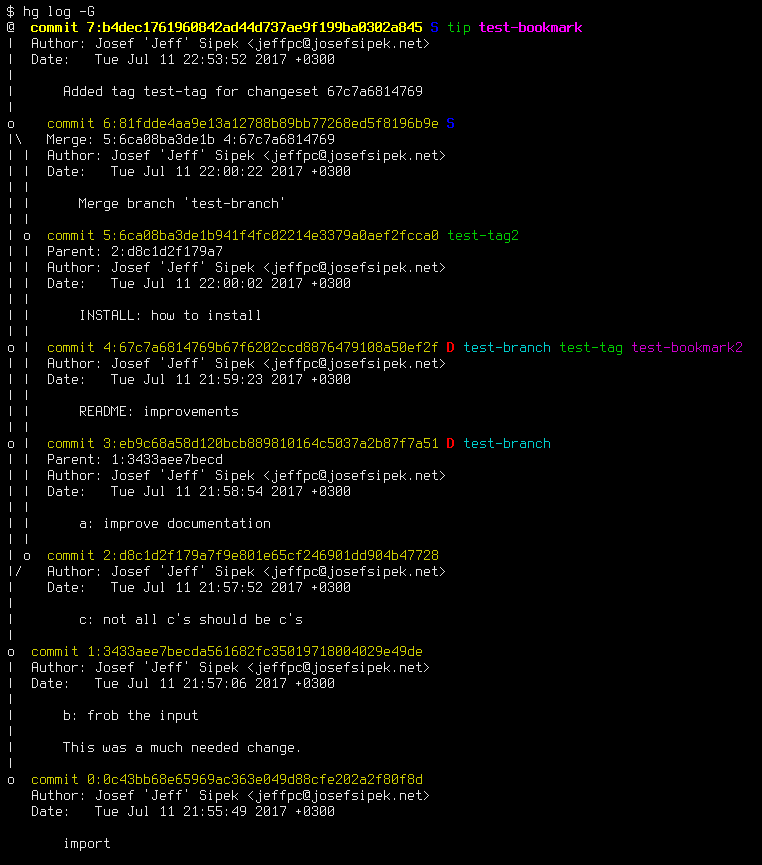

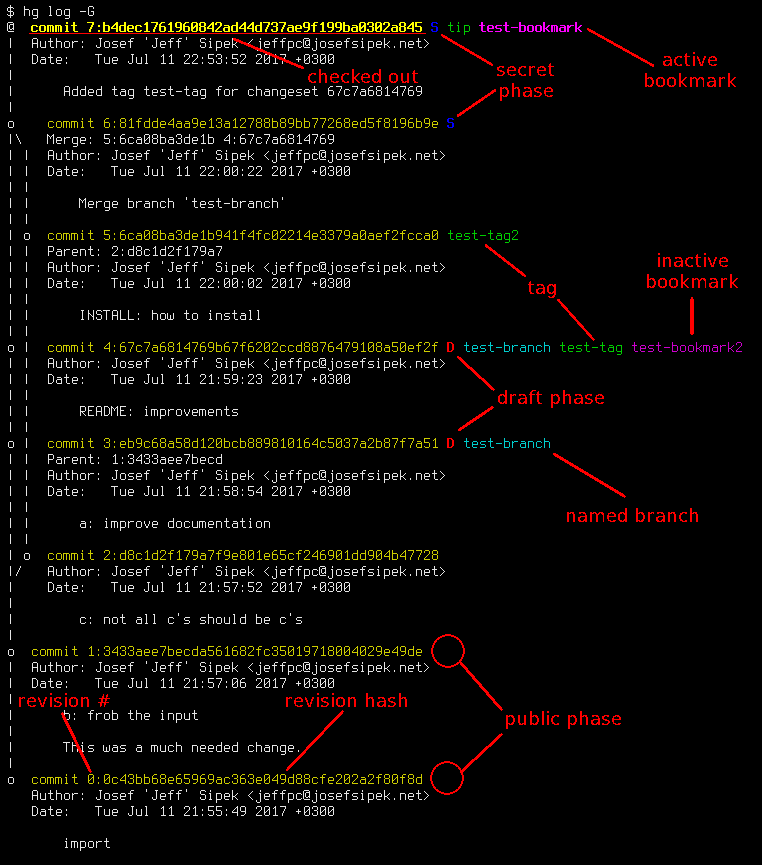

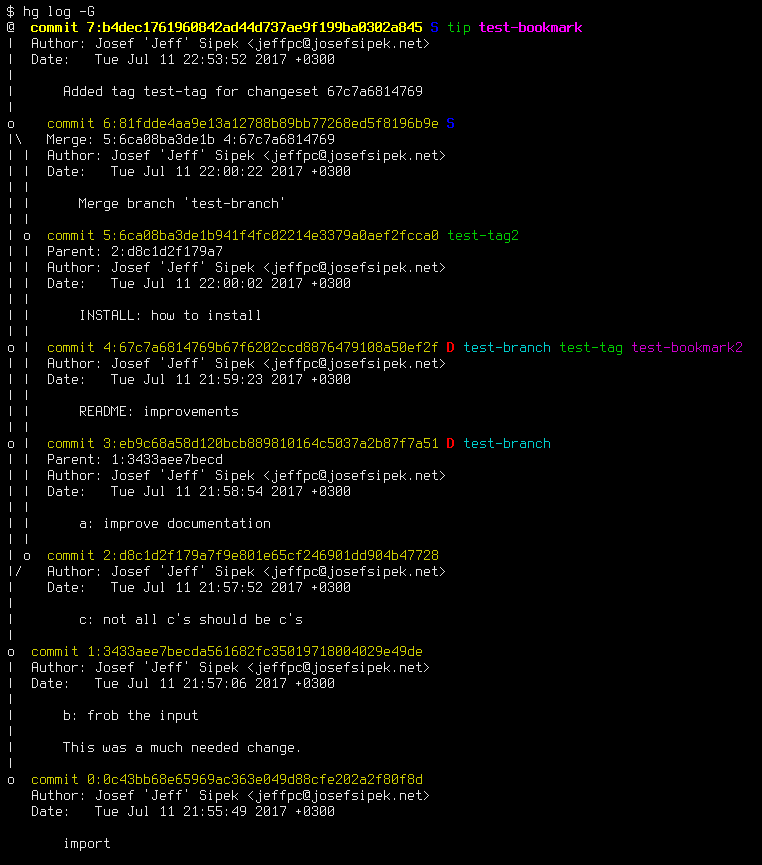

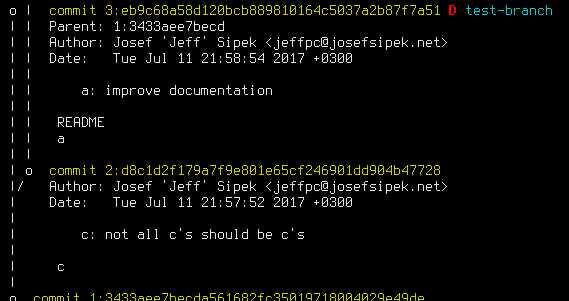

Ok, before I dive into the rather simple config file changes, let’s take a look at a screenshot of the result on a test repository:

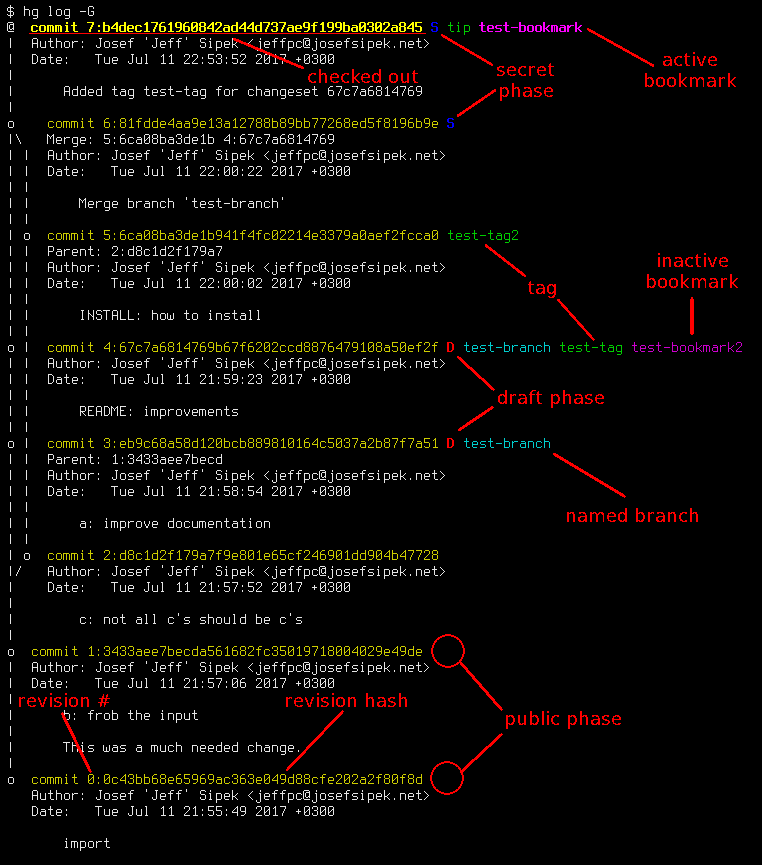

As you can see, the format of each log entry is similar to that of git log (note that the whole multi-line commit message is displayed, see revision 1), but with extra information. What exactly does it all mean? I think the best way to explain all the various bits of information is to show you an annotated version of the same screenshot:

I’m now going to describe the reasons why the various bits of information are presented the just way they are. If you aren’t interested in this description, skip ahead to the next section where I present the actual configuration changes I made.

Each commit hash (in yellow) is followed by a number of “items” that tell you more about the commit.

First is the phase. The phase name is abbreviated to a single letter (or no letter for the public phase) and color coded. It is the first item because every commit has a phase, the phase is an important bit of information, and the “encoded” phase info is very compact.

The reasoning behind the phase letters and colors is as follows:

- public phase (no letter)

- Public commits are not interesting since everyone has them, so don’t draw attention to them by omitting a letter.

- secret phase (‘S’)

- The only interesting thing about secret commits is that they will not be pushed. That means that they cannot be accidentally pushed either. Since this behavior is “boring”, use dark blue to indicate that they are different from public commits, but do not draw too much attention to them.

- draft phase (‘D’)

- These are the “dangerous” commits. Pushing them will change the remote repository’s state, so draw significantly more attention to these by using red.

I use letters instead of just using a different color for the commit hash for a very simple reason—if colors aren’t rendering properly, I still want to be able to tell the phases apart.

Second comes the named branch. When looking at several commits (e.g., hg log), most of the time any two adjacent commits will be on the same named branch. On top of that, each commit belongs to exactly one named branch. Therefore, even though the named branch name is not a fixed field, it behaves as one. In my experience, it is a good idea to display fixed fields before any variable length fields to make it easier for the eyes to spot any differences. (Yes, technically the way I display the phase information is not fixed width and therefore the named branch will not always start in the same column, but in practice adjacent commits tend to have the same phase as well, so the named branch will always be in a semi-fixed position.) Note that in Mercurial the “default” branch is usually rendered as the empty string, and I follow that convention with my template.

Third comes the list of tags. Each commit can have many tags. This is the first item on the line that can become unreasonably long. At least in the repositories that I deal with, there aren’t very many tags per commit, so I haven’t seen any bad effects.

Fourth and final comes the list of bookmarks. Much like tags, there can be many, but in practice there are very few. Since I deal with tags more often than bookmarks, I put the bookmark information after the tags. The active bookmark is rendered as bold.

The choice of colors for named branches (cyan), tags (green), and bookmarks (magenta) was guided by a simple principle: they should go well with the yellow color of the changeset line, and not draw too much attention but still be visually distinct. Sadly, on a terminal without color support, they will all render the same way. I think this is still workable, since repositories have conventions for branches/tags/bookmarks naming and therefore the user can still guess what type of name it is. (Worst case, the user can consult other hg commands to figure out what exactly is being displayed.)

The checked out commit and the active bookmark being rendered as bold without any additional indication that they are different is also unfortunate. I haven’t found a pleasant way to render this information that would convey the same information on dumb terminals. (Note that there is a class of terminals that support bold fonts but not different colors. Even those will render this info correctly.)

Config

So, how did I achieve this glorious output? It’s not too complicated, but it took me a while to tune things just to my liking.

First, I make a custom style file with two templates—changeset and changeset_verbose:

changeset_common = '{label(ifcontains(rev, revset('parents()'),

"log.activechangeset",

"log.changeset"),

"commit {rev}:{node}")}\

{label("log.phase_{phase}",

ifeq(phase, "public",

"",

" {ifeq(phase,"draft","D","S")}"))}\

{label("log.branch", ifeq(branch, "default", "", " {branch}"))}\

{label("log.tag", if(tags, " {tags}"))}\

{bookmarks % "{ifeq(bookmark, currentbookmark,

label('log.activebookmark', " {bookmark}"),

label('log.bookmark', " {bookmark}"))}"}

{ifeq(parents,"","","{ifeq(p2rev,-1,"Parent: ","Merge: ")}{parents}\n")}\

Author: {author}

Date: {date(date,"%c %z")}\n

{indent(desc," ")}\n'

changeset_files = '{ifeq(files, "", "", "\n {join(files,\"\n \")}\n")}'

changeset_verbose = '{changeset_common}{changeset_files}\n'

changeset = '{changeset_common}\n'

Normally, changeset is used by hg log and other revision set printing commands, while changeset_verbose is used when you provide them with the -v switch. In my template, the only difference between the two is that the verbose version prints the list of files touched by the commit.

Second, in my .hgrc, I define the colors I want to use for the various bits of info:

[color]

log.activebookmark = magenta bold

log.activechangeset = yellow bold

log.bookmark = magenta

log.branch = cyan

log.changeset = yellow

log.phase_draft = red bold

log.phase_secret = blue bold

log.tag = green

Finally, in my .hgrc, I set the default style to point to my style file:

[ui]

style = $HOME/environ/hg/style

That’s all there is to it! Feel free to take the above snippets and tailor them to your liking.

hg log -v vs. hg log –stat sidenote

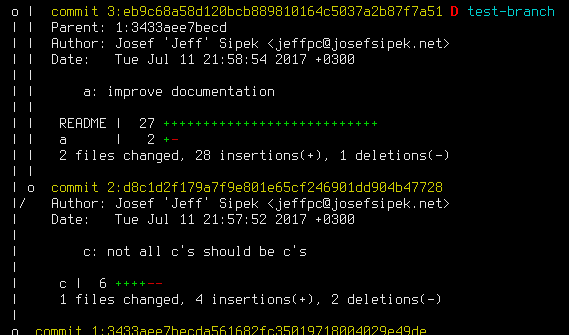

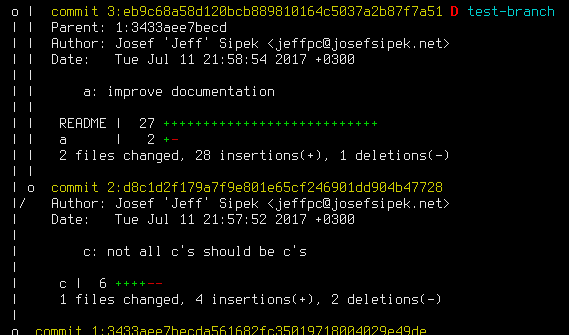

My first version of the template did not support the verbose mode. I didn’t think this was a big deal, and I simply used hg log –stat instead. This provides the list of files touched by the commit and a visual indication how much they changed. For example, here’s a close up of two commits in the same test repo:

Then one day, I tried to do that on a larger repo with a cold cache. It was very slow. It made sense why—not only did Mercurial need to list all the commits, it also needed to produce the diff of each commit only to do some basic counting for the diffstat.

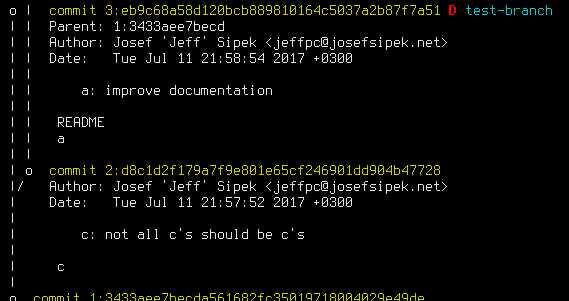

My solution to the problem was to make verbose mode list all the files touched by the commit by using {files}. This is rather cheap since it requires consulting the manifest instead of calculating the diff for each commit. For example, here are the same two commits as above but in verbose mode:

It certainly has less detail, but it is good enough when you want to search the log output for a specific file name.

Hobbs vs.

Hobbs vs.  tach time since I pay based on tach time.

tach time since I pay based on tach time.